By Murray Hunter

BANGKOK, Thailand--The recent imprisonment of former Prime Minister Najib Razak when his conviction was upheld by the Federal Court, and the subsequent conviction of his wife Rosmah Mansor on corruption charges has likely triggered a tipping point in Malaysian politics.

Until Najib’s incarceration and Rosmah’s conviction, the United Malays National Organization-dominated government now led by Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yakoob looked like achieving a landslide in the coming general election, due by September 2023.

Although both Najib’s jailing and Rosmah’s conviction were expected, the pictures of Najib being physically escorted to Kajang Prison and a slumped, masked Rosmah receiving the verdict brought the realization that the rule of law had prevailed. With a long parade of other UMNO officials headed for the dock, there has been nothing less than a political earthquake that has riven the party and rejuvenated the opposition.

The judiciary, particularly Chief Justice of the Federal Court Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat, have been held up as heroes by Malaysians. The gravity of the criminal deeds orchestrated by Najib and Rosmah, particularly with social media pictures and videos of their displayed loot, seem to have sunk in to Malaysians generally, as most witnessed the dramatic events unfolding on national television.

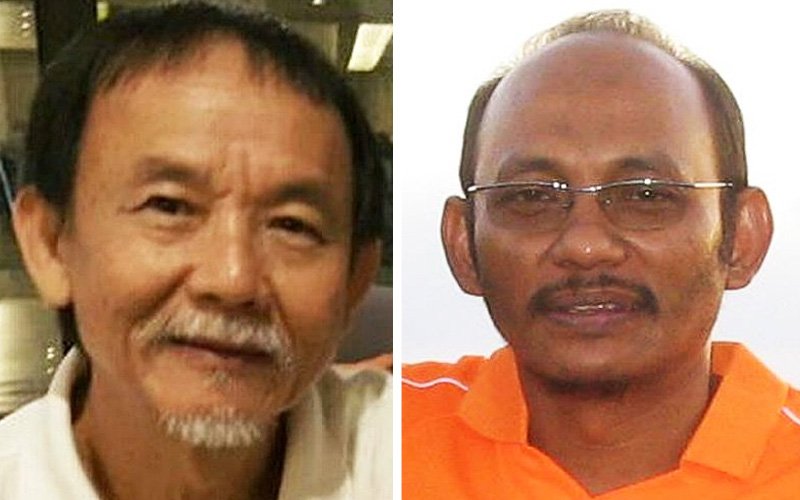

This realization is set to be reinforced by a number of other high-profile cases involving UMNO stalwarts over the coming months. The trial of UMNO President Ahmad Zahid Hamidi is expected to result in a guilty verdict in the not-too-distant future. He faces 47 charges including Criminal Breach of Trust (CBT), money laundering and corruption. Abdul Azeez Abdul Rahim, an UMNO Supreme Council member and Chairman of Tabung Haji, is due to receive a verdict on corruption and money laundering charges soon as well.

Shahrir Abdul Samad, the former chairman of the Federal Land Development Authority, is currently on trial for money laundering, and former Dewan Rakyat Speaker and current Kinabatangan MP Bung Moktar Radin and his wife have been ordered by the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court to answer corruption charges.

UMNO now on the back foot

Malays have been told for generations that they must vote for UMNO out of gratitude. The party’s control of the education system and mainstream media over decades have enabled the government to engineer the narrative that ethnic Malays, who make up a majority of the population but who continue to lag economically despite decades of affirmative action programs, must be obligated to UMNO.

This has been an implied social understanding between UMNO and Malay-centric electorates that kept the party and its ethnic partners in power from before Merdeka until the 2018 general election, when they lost to the reform Pakatan Harapan coalition.

Former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad was able to challenge this ‘social understanding’ by portraying Najib as a corrupt leader, with voters no longer required to feel obligated to vote for UMNO.

Since the fall of the Pakatan government in February 2020 and its replacement with a Malay-centric coalition then headed by Muhyiddin Yassin, support for Pakatan fell sharply, as seen in both the Melaka and Johor State election results which returned Barisan candidates by big margins.

Given those results, most political pundits wrote off Pakatan as having little chance to take back the government. There were predictions that Pakatan could lose up to one-third of their seats, with Anwar Ibrahim’s Party Keadilan Rakyat, or PKR hardest hit.

Najib, even though convicted of 12 counts of corruption in 2020, played the role of ‘prime minister in waiting’, wielding great power with Zahid within UMNO. This power has dramatically evaporated since his jailing, leaving Zahid in a very weak position. The rage within some of UMNO’s rank and file that Zahid was able to generate on the day of Najib’s jailing had mostly disappeared by the day Rosmah received her guilty verdict.

Zahid appears to now be on borrowed time. The reality of a potential criminal conviction is setting in with his support base quickly dispersing.

Ismail Sabri, on the other hand, who was verbally attacked by Zahid supporters and had to arrive at the UMNO headquarters in an armored convoy on the evening Najib was sent to Kajang Prison, only has to be patient before he is in a position to take control of the party.

With brand UMNO badly damaged, Ismail Sabri has two basic choices. The first is to wait until Zahid is convicted, if he is, with a verdict expected before the first of the year, and go for a full takeover of UMNO. Most UMNO warlords are expected to fall into line, enabling Ismail Sabri to announce an immediate reorganization, regenerating UMNO’s branding into something acceptable to the Malay electorate. This would be welcomed both in the Malay heartlands and make UMNO or other Barisan Nasional, or BN contenders competitive in mixed seats.

The second option, deeply unlikely, is to distance himself along with his cabinet from UMNO and go with a new Malay-centric coalition, distancing him from the wreckage of an indelibly corrupt party with a new electoral force. Any metamorphosis of UMNO would appeal to many, easily making Ismail Sabri the winner, with the support of the governing GPS coalition in Sarawak, and UMNO Sabah.

Both scenarios most probably mean a general election later, rather than sooner.

A New Chance for the Opposition

The opposition forces have been dealt a new set of cards. The coming general election is potentially winnable, if they play them right. This is a dramatic change in fate, which should prevent them being decimated as many predicted, in the coming general election.

However, the opposition cannot by any means be complacent. UMNO is still a very strong adversary. It will be beaten by hard and smart electioneering. The party and its coalition components are long practiced in the art of using government largesse and copious funds in the rural hustings. The greatest danger for the opposition forces is if they are splintered by a large number of new political parties, with potential three- or even four-cornered electoral fights that would cost them dearly.

The opposition priority must now focus on creating a candidate lineup that wouldn’t waste votes. It can’t rely on any bonuses from the youth vote. Many have been indoctrinated through education and other social institutions and want a Malay-centric state, something they see as more important than opposition-pledged reforms. They may be sympathetic towards a new Malay-centric front or a reformed UMNO. Gaining the youth vote will be a massive challenge for the opposition.

The most likely result with a good opposition performance is that no single grouping will have the numbers to govern. Pakatan will have to look very closely at potential scenarios. It needs to revise its geriatric leadership. The effectiveness of the Anwar Ibrahim-Rafizi Ramli relationship, if there is one, will make or break Pakatan. So far, Anwar shows little inclination to give way to the younger, politically savvy Rafizi.

The ideal election would be a reborn UMNO versus a recalibrated opposition. It will be interesting to see if that happens. The alternative is a rebirth of the deeply corrupt UMNO versus an aging, indecisive opposition. There are few who would want to see the political revolution die that way.

0 Comments

LEAVE A REPLY

Your email address will not be published